New Documentary ‘Summer of Soul’ Spotlights Historic Harlem Music Festival

The year 1969 won’t soon be forgotten. Even though it is more than 50 years in our past, it was a time of social upheaval that changed our nation forever. 1969 gave us a historic moon landing, the Vietnam War, and three days of peace, love, and happiness known as Woodstock. But what a lot of people don’t realize is that there was another music festival that summer just as important that went largely unnoticed.

The historic Harlem Cultural Festival as it was known is the subject of a new documentary being released in theaters this weekend called Summer of Soul. Featuring musical artists such as Stevie Wonder, The Fifth Dimension, and Gladys Knight and the Pips, the film seeks to capture the healing power of music during a time of racial unrest.

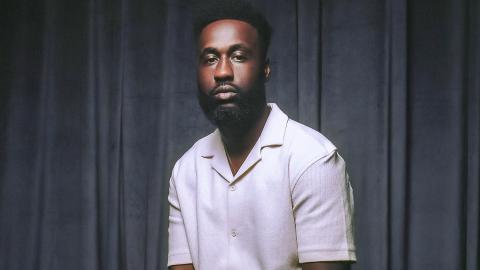

Best known as Jimmy Fallon’s bandleader on The Tonight Show, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson makes his directorial debut, taking viewers on an exploration of a watershed moment that still holds merit in the present day.

During an interview with CBN.com and other reporters at a recent press conference, Thompson shared about the impact that gospel music had on the Harlem Cultural Festival, the perceived erasure of Black History, and how this event socially effected the lives of so many.

Can you tell us about how you first learned about the footage that would eventually become the basis for Summer of Soul?

I first inadvertently saw the footage back when (my band) The Roots went to Tokyo in 1997. My translator for that tour who knew I was a soul fan, took me to a place called The Soul Train Cafe. Unbeknownst to me, I was watching two minutes of Sly and the Family Stone’s performance. It was like a bird's eye view, a view from the nosebleed section. I didn't know I was watching the Harlem Cultural Festival. I just assumed that all festivals in the Sixties were from Europe, because America really didn't have that culture yet. I found out exactly 20 years later when David Dinerstein and Robert Firestein told me that they had this footage and they wanted me to direct the film. So, I first saw it without knowing it in 1997 and then it was presented to me in 2017. But even then, I didn't believe it was a real.

What part of the process in making this film did you feel the greatest shift in yourself as an artist and storyteller? Was it looking through the footage, interviewing talent festival attendees, piecing it all together, or the dialogue you've had with those who've seen your film?

Without being all touchy feely with it, this project more than anything has helped me develop as a human being. For all the journalists out there, you know that sometimes artists can be really neurotic, living inside our heads. It's kind of weird that even though I wrote the “Creative” course book. There was one point where I caught myself going back to through chapters five through eight, mainly dealing with how creativity is transferable. I will not hesitate to admit that of all the things that I've done creatively, this is the one that I was really nervous about. And by nervous, I mean scared. That is partly because I'm a perfectionist. What I will say is that this film has really brought out an awareness and a confidence in me that I never knew that I ever had.

Why did you choose to focus much of the film on gospel music and the faith that has been in the background, if not the foreground of some performers?

That's a weird way to look at it. As far as I'm concerned, there was a perfect balance of soul music, free jazz, and salsa music. The one genre that I truly left out was comedy because it would've taken me a good 20 minutes to really make sense of how the humor of the day worked for that audience and why they were killing (making people laugh). For me, the gospel aspect of it, I kind of saw gospel and free jazz as one in the same. I'm a guy that's always doing litmus tests with people, as far as testing music out on them.

There's no time in which I'm presenting music in which I'm not conducting an experiment. You just think that I'm deejaying, or you just think that I happened to put the song on, but I'm really looking for reactions to see what people respond to. But there's one thing I always noticed. When I play really intense soul music for younger people, they tend to find James Brown’s yelling humorous. That's funny to them because we live in a meme/gif culture. So, those three seconds of something out of context can seem funny to people. There was a lot of what we can call primal musical expression or primitive exotic expression. Or, to use a layman's term, people acting wild. And I wanted people to know that this was more of a therapeutic thing than anything. And for a lot of us, gospel music was the channel, because we didn't know about dysfunctional families, therapy, and life coaches that we have now.

As a disc jockey you're someone who tells stories via music. Were there parallels between using those muscles, mixing music, and the discipline in which you approach this wealth of footage, assembling it in a way that it tells a story and has a narrative balance?

For starters, for five months I just kept (the festival music) on a 24-hour loop, no matter where I was in the house or in the world. If anything gave me goosebumps, then I took a note of it. I felt like there were at least 30 things that gave me goosebumps. So, that created a foundation. I tend to work backwards whenever I'm given a project. The first thing I think about is the last 10 minutes of the show or the set that the person takes home with them. (A moment where you say,) man, that was incredible. Usually, the last 10 minutes of a show or a presentation is your chance to capture your audience.

I figured that was the best way for me to crash land into your lives as a director, without it really being about me was to feature Stevie Wonder performing a drum solo. And we have not seen Stevie Wonder in this light as a drummer. So, I thought that was the perfect beginning and that's pretty much how I crafted the show. I searched for my ending. I knew I wanted what my beginning was and then I worked backwards.

How much work did it take to make the audio work as well as it did in the final cut of the film?

We had to do maybe 2% worth of adjustments on the audio. The audio that you hear with the music is the dry, rough mix from the soundboard. It sounded perfect. And for the life of me, I can't figure out how 12 microphones were utilized in a way so powerful, especially when three of those microphones from Stevie Wonder’s performance are on his drum set that he only uses once. And the other three were on his other drummers. So, six microphones were used for two sets of drums. The other six were used for Stevie's vocal, one mic for the amplifier for the guitar and the bass combined, and the rest were used for the orchestra. And I'm trying to figure out for the life of me, why does this sound so crisp and pristine? It's to the point where I'm almost tempted to strip down The Roots ourselves. I called my production manager, telling him, hey, they only use 12 to 15 microphones for this whole production and it sounds perfect. How many do we use? With a straight face he said we use 103 mikes. So, I'm trying to figure out if The Roots as a band could survive with just 15 microphones.

You've talked a lot about the erasure of black history to the way this footage was just disregarded. It seems that the erasure was apparent back in 1969. Woodstock got all the press and the Moon Landing was huge. What are the keys to pushing back on similar erasure today and beyond?

This is a step forward. This is the first time that I'm really seeing conversations that were never had before, especially post-pandemic. We weren't talking about mental health for black people. We really weren't speaking of black erasure. Years before we sort of coded it as cultural appropriation, it was always sort of draped in slang so that you couldn't see the heart or the sincerity of what the problem was. I know this one thing. This isn't the only story out there. Probably the most shocking thing that I've learned in the last month is that I’ve gotten direct messages (DMs) from professors at universities letting me know that they know of concert footage of 20 hours for something that they did in New York.

So, this isn't the only footage that's just laying around unscathed. There is about six to seven others. Maybe this film can be an entry, or a sort of a sea change for these stories to finally get out there, but really for us to acknowledge that, yes, even something as minuscule as content on social media, or one of the first ever black festivals is important to our history. The conversation is being had now. Normally, the process is that we talk about it for three months and then when we forget about it. That will remain to be seen. As for me, I didn't come into this wanting to be a director or any of those things. I do believe that creativity is transferable. This is not my last rodeo with telling our stories. If anything, I'm more obsessed now than ever to make sure that history is correct, so that we don't forget who this artist is, or that event was.

Summer of Soul features the interviews, the big reveals, and especially the Fifth Dimension. Can you talk about your reactions to their reactions and how that shaped the film emotionally going forward?

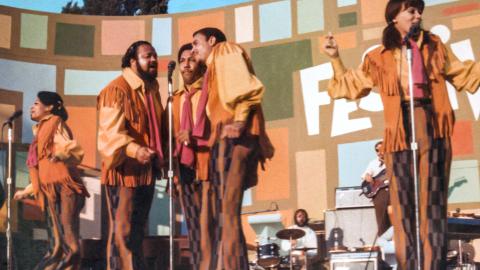

The emotional component of the film was something that I wasn't prepared for, and really didn't know what was going to happen. That emotional trigger moment, at least for the Billy Davis Jr. and Marilyn McCoo portion, was the fact that I noticed that I couldn't quite put my hand on it, but my memory of all the Fifth Dimension performances I saw were composed, steady, very posh, and sophisticated.

This performance of theirs at the Harlem Cultural Festival was closer to that of a gospel revival. I've never heard Billy Davis, Jr., with the exception of one of their songs on their solo records called “Like Your Love.” I had never heard Billy Davis Jr. use a raspy gospel baritone. It sort of had a James Brown quality to me. I thought it was humorous. I was like, wow, Billy, I've never heard you use your gospel register before. They kind of opened the door and said, “It was the kind of a cause where we were comfortable and excited to be there, but there wasn't a pressure of we're on the Ed Sullivan Show or Jack Parr’s Tonight Show.” I realized I had a momentum of movement as they're describing this one.

Probably the most telling moment of that festival that goes over people's heads was when I'm looking at David Ruffin's performance. It's the middle of August and he's wearing a wool tuxedo and a coat. And I'm like, why? Then it hit me. Back then you had to be professional even to the detriment of your own comfort. Meanwhile, the most revolutionary performance to that audience, nothing will beat watching camera four of the of Sly and the Family Stone’s performance. Their outfits were very different. The audience had never seen a black act, not wear a tuxedo.

I want to mention Musa Jackson. He was five years old at the time. And I thought what five-year-old is going to give me insight of the emotional deepness of being there when he's that age? The thing that won us over was that he said this was my first memory ever, but he wasn't sure he had it.

He definitely remembers. Once we showed him the footage, suddenly the tears started welling because for him, as a 57-year-old, he didn't know if he remembered it. He didn't know if anyone believed him. If I didn't believe this happened as an adult, who's going to believe a five-year-old who says he saw Sly and the Family Stone and Nina Simone all in the same week in Harlem? He knew this happened. That's why he started crying. So, I didn't realize there was a heavy emotional component until we allowed people to give commentary. And I'm so glad we made that decision instead of not doing that.

Watch a Movie Trailer for Summer of Soul: